An investigation into the brain science behind rituals in the office, and how they can make teams stronger and more productive.

Note: This project is the first installment in #workbeautiful, a content series where we explore what it means to "work beautiful," be it productivity, design, psychology, and the future of work — brought to you by Beautiful.ai (cloud software that designs your presentation for you in real time). Feel free to view this project as a slideshow, view the full length video interview with guest presenter and Bay Area journalist Katie Morell, or continue reading below — your choice. We hope you benefit from what you learn (and share with those you think could benefit as well).

An Investigative Report on Rituals in the Workplace

Fast Food Fridays: The Beginning of Something Special

It was around 5:30 p.m. on a Friday in December 2017 when Dina Chaiffetz decided to make a pit stop at a place she rarely visits: McDonalds. Based in San Francisco, she was commuting 85 miles round trip for the third Friday in a row, for a 10-month project based in the East Bay city of Fremont. A few weeks in, she had many more Fridays to go.

In the back seats of the rented UberXL were her colleagues, together comprising a team of consultants from Prolific Interactive, a mobile strategy and design firm with offices in Brooklyn, San Francisco and Durham, North Carolina. As director of product strategy, she was overseeing the project taking her and her team to Fremont every week. And, as exciting as the work was, she was noticing an energetic downshift come late Friday afternoon. “I started wondering what I could do to make things more fun, and decided to take a page from my personal life and treat the rides home like road trips,” she says. “And when I’m on a road trip, I like to eat fast food.”

Fries, happy meals and burgers in hand, the team ate the whole ride home. Friday’s dinner wasn’t discussed again until the end of the following week, when Chaiffetz offered to take the team to a Carl’s Jr. Her colleagues perked up at the suggestion, and off they went. This quickly became the norm and soon the restaurant decision was being rotated between team members.

All of a sudden, regular client meetings in Fremont were no longer associated with cringe worthy traffic and grumbling stomachs, but instead dubbed ‘Fast Food Fridays.’ “By the end of it, we were talking about developing a sauce-rating system,” Chaiffetz laughs.

Perhaps without knowing it, Chaiffetz had created something of a sacred ritual among her team. The result was strong team cohesion and a mood of lightness throughout the entirety of the assignment.

Not So Trivial: The Case for Being Silly

While this example may seem inconsequential, it represents a field of study—rituals and how they can impact team dynamics—that is taking off as of late. It also poses several questions, among them: How can rituals in the workplace impact struggling teams? What happens to our brains when we do a ritual? Why should we care about rituals in our professional lives?

Dr. Nick Hobson has made it his life’s work to find several of these answers. Hobson is a neuroscientist from the University of Toronto and founder of The Behaviorist, a behavioral and brain science consultancy. He explains that rituals are hugely powerful to our brains, because humans generally have two modes of thinking: instrumental thinking and ritualistic thinking.

Instrumental thinking is when we do things rationally and related to goals. Think: I want to go to the gym so I can lose weight, or I’m going to work extra hard on a Saturday to finish a project. Ritualistic thinking, on the other hand, is when we do something that doesn’t make any logical sense, but on some level our brains have evolved to know that it's still important — or even vitally important.

There are obviously many examples of ritualistic thinking in religion. Several faiths include ritual songs and even physical actions (standing up, sitting down) as part of ceremonies or weekly gatherings. Examples in the workplace can include going on a yearly retreat with colleagues to the same place and doing the same things while there— eating at the same restaurant the first day, going golfing the second day, and so on.

“When we do these things, our brains say on an unconscious level, ‘I don’t know why this is important, but all I know is that it is important, so I’m going to attach more meaning to it,’” he says.

All of us, even if we aren’t religious, can identify rituals in our lives that are enormously important. I grew up in a non-religious family that celebrates Christmas, and on every Dec. 24th we sit in my mother’s living room and sing carols. This has happened since I was born and if I miss a year, I am deeply saddened and feel like I’ve really missed out.

Rituals are present all over the workplace. Dropbox, the popular file hosting service based in San Francisco, famously sends welcome kits to potential hires in unmarked boxes.

The contents: a picture of a cupcake and the ingredients to make one of their own.

Why would a tech company do this?

“The reason is that delight is one of Dropbox’s core values, and they want their employees to feel delight when they open that box,” says Hobson. “The ritualistic token of delight to them is a cupcake. Interestingly, employees have said that they laugh this off at first because it seems so trivial, but then realize later that this gift, this concept, is core to the company and how it works.”

Compare and Contrast: Ritual or Habit?

So what is a ritual, and what is simply a habit? You go out for coffee every day with your co-workers. You brush your teeth every day. You take your dogs for walks when you get home from work every day. But are these rituals? Not exactly.

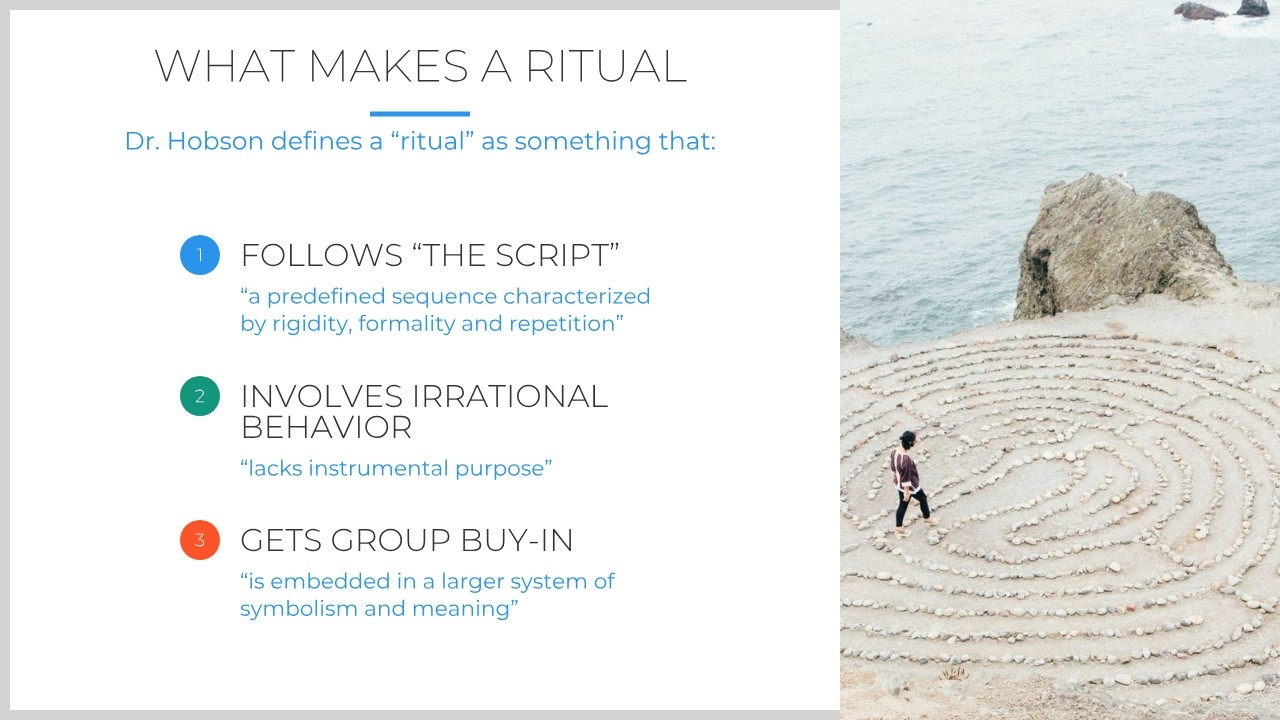

This is a confusing question/answer combo, and one that scientists have been grappling with for decades. In November 2017, Hobson and a few colleagues decided to try to wrangle a clear definition of rituals. The results became an a November 2017 article in Personality and Social Psychology Review titled “The Psychology of Rituals: An Integrative Review and Process-Based Framework.”

Hobson and his co-authors arrived at a concise, three-part definition of rituals. First, in order to be a ritual, there must be a so-called ritual script, or as the article reads, a “predefined sequence characterized by rigidity, formality and repetition.” Second, the action must be more meaningful than a routine or habit. It must be “embedded in a larger system of symbolism and meaning.” And third, it must have some irrationality associated with it, or “lack instrumental purpose.”

That means, if you go to coffee with your co-workers every morning, it would only be considered a ritual if you went at the same time, and to the same place, with the same people, every time. If you felt internally compelled to make this date no matter what, it could be a ritual. But if you go at 10 a.m. some days, 3 p.m. other days and alternate between Starbucks and Seattle’s Best, it’s just a habit.

Also and importantly: everyone must agree to the ritual and willingly do it together.

“Rituals have a social function because they are shared,” says Dr. Cristine H. Legare, associate professor of psychology at The University of Texas at Austin. “Most rituals are done in groups as collective practices. And there is always group buy-in. The amazing thing is that, unlike habits or routines, they have been shown in social psychology to improve everything—from making your food tastier to making you more motivated.”

The Nitty Gritty: Let's Talk About Brain Science

In order to truly grasp the power of rituals, it’s important to look at the brain science working in the background. This topic first piqued my interest not when I was in a conference room, but when I was tearfully saying goodbye to my beloved Grandmother. It was this past summer, and I’d just attended her memorial in Northern Michigan. She had passed in 2017, but, as per family tradition, we’d decided to hold off on her funeral until July 2018 when our entire extended family could attend.

The year leading up to the funeral was emotionally excruciating for me, with bouts of deep grief and many other lows seemingly not related to her death. Something—in addition to my Grandma—was missing in my life, but as someone who was brought up without a religious affiliation, I couldn’t put a name to the need I had.

It wasn’t until her memorial that I realized what I needed was a ritual—a ritual to let her go. When her funeral ended, I picked up my tissues and walked outside a changed person; feeling lighter and happier than I had in a full year. The feeling was something beyond closure. I knew at that moment that something had shifted inside my brain —a shift that had everything to do with the ritual in which I’d just participated.

Months later, that shift is still there. Permanent.

So what’s the deal with the brain and rituals?

Hobson had some ideas. He explains that researchers have long been studying rituals (it is a cornerstone of cultural anthropology) but the actual brain science has been hard to pin down.

“Some of my own research has found that when you do a ritual, the anxiety response in the brain — the signal that is typically associated with negative emotion — becomes muted,” he says. “Rituals help provide order and structure, and a sense of calm and relief. From a neurobiological level, there is a tangible difference in the results when performing any ritual, even if it is entirely made up. And if you perform a ritual across decades, even centuries, as seen in some religions, that can be incredibly powerful psychologically and neuro-biologically.”

"When you do a ritual, the anxiety response in the brain — the signal that is typically associated with negative emotion — becomes muted.” — Dr. Nick Hobson

This made a lot of sense to me, especially when considering the fact that athletes often report doing rituals before games (i.e. LeBron James’s chalk toss; Michael Jordan wearing his college shorts under his Bulls uniform; Michael Phelps eating chicken nuggets before every race).

“Rituals quiet the mind; they get us comfortable. All the best [athletes] have pregame rituals,” says Dr. Rob Bell, an Indianapolis-based mental toughness coach who works with professional sports teams and Olympic Athletes. He says his own ritual — sitting down to write every day between 5:30 a.m. and 6:30 a.m. — has helped his performance. To date, he’s authored six books out of those morning sessions.

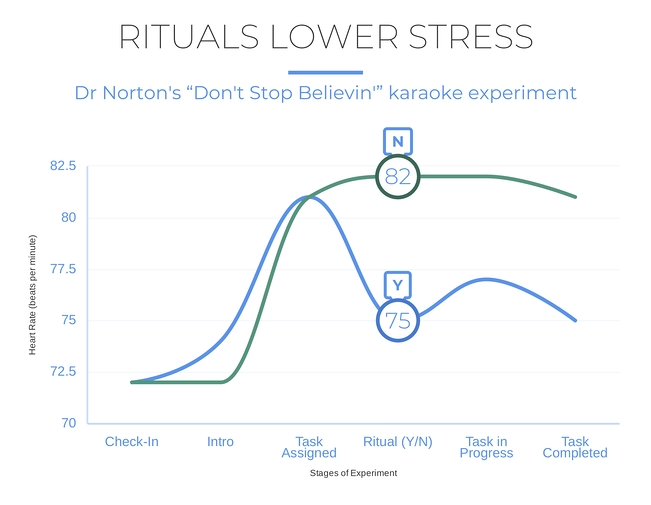

Now deep in the ritual rabbit hole, I called up Dr. Michael I. Norton, Professor of Business Administration at Harvard Business School. Back in 2016, he and a few of his colleagues performed a study where they asked people to sing Journey’s “Don’t Stop Believing” karaoke-style, and told them they’d be graded on their performances in real time.

Talk about stress city.

Norton gave each person a ritual to do before going on stage. The rituals were completely arbitrary, like clapping ones hands or snapping ones fingers a few times.

“We found that doing a ritual reduced their anxiety and allowed them to perform better on the song,” says Norton.

The results, which became the article “Don’t Stop Believing: Rituals Improve Performance by Decreasing Anxiety,” were published in the November 2016 issue of Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes. It found that, as Norton says, “Rather than just telling yourself to calm down, which causes more anxiety, the orderliness of the ritual itself is calming. We found that doing a ritual reduced participants’ anxiety and allowed them to perform better on the song.”

The Point Being? (Why Business Leaders Should Care About Rituals)

Kursat Ozenc is keenly interested in how rituals specifically impact workplace teams. After earning his Ph.D. in design — with a focus on the effectiveness of rituals on people in transition — from Carnegie Mellon University in 2011, he moved to the Bay Area in 2013 and got a job with software giant SAP. Enjoying his new role, but missing his previous academic life, he decided to co-found Ritual Design Lab to, as he says, “To help keep his work alive.”

The Lab, per its website, consists of “interaction designers researching the power of rituals to build value, meaning and community into our everyday experiences. This Lab is a research initiative that particularly focuses on organizational culture building.” Ozenc and his co-founder, fellow designer Margaret Hagan, do this by partnering with The Stanford d.school to create twice-yearly pop-up classes (a.k.a. workshops) where Stanford students put together rituals for outside companies.

“We design rituals for teams so they can function better and be more creative,” says Ozenc.

SAP’s design team was one such group that went through the process. Students recommended the team change its onboarding process for new employees to a model that included more personal sharing. The Lab suggested that on an employee’s first day, their desk be decorated with objects that belong to fellow team members. It is then their job to find out what object belongs to whom.

“It’s like a treasure hunt. For this ritual, the new hire tries to understand who owns the object and the story behind it."

— Kursat Ozenc

“We often put our favorite objects on our desks," says Ozenc. "Maybe someone has a miniature elephant from a trip to Thailand, or a picture of a loved one. For this ritual, the new hire tries to understand who owns the object and the story behind it."

What have been the results of the ritual? Was it successful?

“One measure we look at is whether or not the ritual is still ongoing,” says Ozenc, "and it is — after almost two years. So it is working." He goes on to explain that, due to the intrinsic, irrational definition of a ritual, it is difficult to measure the impact. And studies that cite ritual efficacy can be pretty subjective. However, it doesn't seem a coincidence that some of the most successful companies, with the highest reported employee satisfaction in the world, have adopted a strong ritual culture.

For instance, at architecture and interior design platform Houzz, employees tell of company-wide "Sip and See" events (new baby meet-and-greets), where any staff member who has welcomed a new child into their family in the last 6 months brings in baby for their coworkers to fawn over. There are empty baby bottles to fill with a variety of colorful pastel candy, formal intros of each baby, and an internal eblast with adorable photos of each new family member with their current "likes" and "dislikes."

At Airbnb, employees describe a send-off ritual for fellow employees that are transitioning out of the company after a meaningful tenure: Staff create an insanely long human tunnel in the main lobby, which the departing employee then runs through — accompanied by the occasional confetti bomb and shouts of encouragement: "We'll miss you!" "Best wishes!" "Keep in touch" et cetera.

Presentation software company Beautiful.ai — based in the Mission district of San Francisco — welcomes new staff members by asking them to give an introductory "About Me" presentation highlighting their unique interests, personal background and professional goals. The presenting employee also gets to choose the catered lunch cuisine for that day, as a way to pay homage to their ethnicity, travels, or simply their favorite food.

Wide Angle: Our Societal Need for Rituals

Take one look at the U.S. job reports and you will see that our country’s unemployment is impressively low. In September and October 2018, the rate hovered at 3.7 percent, the lowest it’s been since the late 1960s. While this is excellent news for job seekers, it can spell headaches for employers looking to attract and retain talent.

In today’s marketplace, culture is everything. Without a good company culture, employees are quick to fly the coop for a better “fit.”

This is where rituals come in. “Usually, the most important rituals are tied to a company’s values,” says Hobson. “Business leaders need to make values more tangible and you can do that through rituals. It makes something abstract more concrete. You can share the physical meaning.”

As Dr. Legare explains, rituals are a core part of group-living and human behavior: “We live in groups and have to solve problems working in groups,” she says. “Rituals increase cohesion within groups.”

“We live in groups and have to solve problems working in groups. Rituals increase cohesion within groups."

— Dr. Cristine Legare

But what about the fact that so many rituals seem frivolous? Should all business owners, even those who are time and money-strapped, invest in creating rituals?

Yes, Hobson argues. He says in our society of “hyper-productivity” it can be easy to see rituals as an economic waste.

“Why should we do some silly behavior when we could be doing Q4 financials?” he asks, facetiously. “Because the downstream byproduct of engaging in rituals is multifold: including tighter groups that bond together; groups that are emotionally regulated and can respond to the ups and downs of pressure; and groups that are more motivated —just look at high performing athletes after they engage in rituals.”

Marching Orders (Creating a Ritual in Your Workplace)

Back at Prolific Interactive in San Francisco, Chaiffetz believes that the most effective rituals are those created by small teams.

“It makes it more powerful when the ritual is generated by everyone on the team, rather than top down from the c-suite,” she says. “It ends up being a fantastic morale tool.”

So what goes into making the perfect workplace ritual?

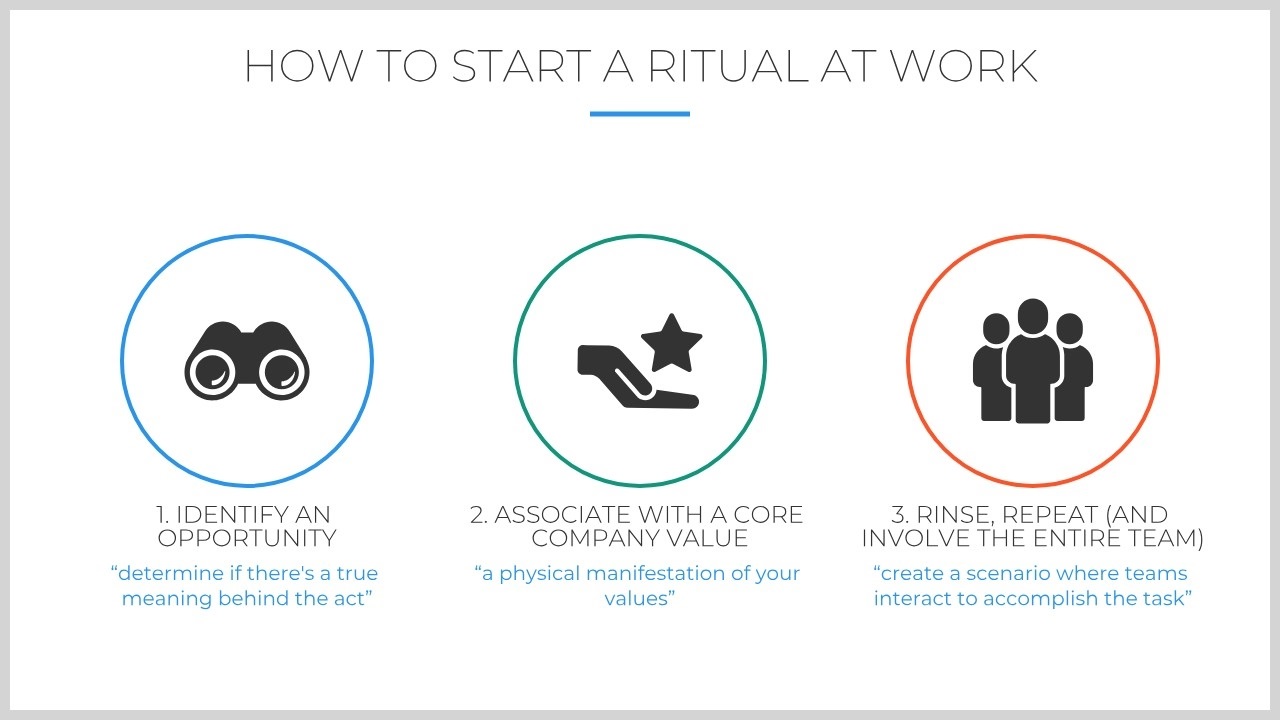

Ritual Design Lab’s Ozenc says it's best to first identify a moment in the lifecycle of something at the office, be it the beginning of a project, the onboarding or departure of an employee or even the start of a meeting. From there, try to tie the ritual into a core company value. Then, it’s important to follow a set script, so the ritual can be repeated. “Invest meaning in that familiarity, and it will catch on,” Ozenc says.

One important distinction: to be a ritual, it needs to be physical.

“Rituals are born out of physical proximity, which can present problems with online businesses and remote workers,” says Hobson.

He advises leaders bring employees together, ask them to solve a problem, and then see what happens. This often happens in corporate retreats. The longer a team works together, the more likely they will be to create organic rituals as part of the collaboration process.

“Rituals will naturally expose themselves,” he says. “The job of a manager is to spot those rituals beneath the surface and facilitate their emergence. You are looking out for some level of non-instrumentality, some element of silliness. These are things that arise spontaneously and may be completely unrelated to the work at hand, but will help your team be much more productive in the long run.”

View this article as a slideshow below or watch the full length video.

.avif)

.avif)

.avif)